Cette série est dédicacée, tout particulièrement, à mon amie Sarah, photographe qui rêve de Namibie.

Pour rencontrer Nick Brandt, il faut surtout de la patience parce que ce photographe est extrêmement occupé et demandé. A titre d’exemple, son dernier projet « A Shadow Falls » a été exposé dans trois capitales européennes en seulement dix jours. La patience de Lesphotographes.com a fini par payer : nous l’avons rencontré à Bruxelles juste avant son départ pour Paris. Nick Brandt est un photographe avec une passion sincère pour son sujet : les animaux africains. Il ajoute de la romance et de l’intimité pour élever ce genre très connu de la photographie à un nouveau standard. Avec nous, Il a pris son temps (et raté son train), pour partager ses pensées, son travail, et la condition des animaux africains.

INTERVIEW :

Voyez-vous votre projet récent « A Shadow Falls » comme un testament qui décrit les animaux africains, ou comme un travail qui doit motiver les peuples à protéger ces animaux ?

Pour moi, c’est un dernier testament. Ces animaux disparaissent mais ceci ne veut pas dire qu’il faut les abandonner. Comme dans le cas du réchauffement climatique, tout le monde avec un tant soit peu de jugeote sait que ça existe et que ça s’empire. Il ne faut pas perdre espoir, on peut toujours faire quelque chose. Ces animaux disparaissent tellement vite et cette situation va tellement en s’empirant, que nous sommes obligés de faire quelque chose. Je documente ce monde comme il est aujourd’hui, et peut-être comme il ne sera jamais plus. Je souhaite que les gens s’engagent comme ils le peuvent. Moi, je ne suis qu’un seul élément de l’action qui peut être faite. On peut être environnementalistes, ou photographe par exemple. Chacun de nous essaye d’informer les autres.

Cette façon de présenter les animaux varie de ce dont nous avons l’habitude. Nous pensons à des photographies de lions, prises sur le vif, avec beaucoup de couleur par exemple. Quand vous avez commencé à photographier, aviez-vous déjà pensé à prendre vos photos comme des portraits et en noir et blanc ?

Je ne me suis jamais pensé comme photographe de nature. Même en tant que touriste en Afrique, avant que je commence ce travail, j’avais mon Pentax 67, je photographiais déjà en noir et blanc et je détestais le 35mm. Depuis le début, et dans mon premier livre, il y a quelques photos des dix premières pellicules que j’ai faites en Afrique. Si vous regardez toutes mes planches contact, il n’y pas de photos d’action faites au téléobjectif. En fait, j’ai acheté un petit téléobjectif, je l’ai utilisé pendant quelques jours, puis je l’ai rangé pour de bon.

Tout votre travail est fait avec un Pentax 67, un objectif court ?

Oui.

Comment vous approchez-vous des modèles avec un objectif court ? Est-ce facile ?

Non, mais ça dépend – chaque animal est différent et on ne peut jamais savoir. La vraie difficulté est que les endroits où je peux m’approcher des animaux deviennent de moins en moins nombreux parce que leur habitat est détruit. Tous ce qui reste sont les parcs et parce que les touristes vont dans ces mêmes parcs, c’est donc de plus en plus difficile pour moi d’être seul avec les animaux. Et je ne peux pas être près des animaux quand il y a d’autres gens: je leur gâche la vue et c’est un peu antisocial! Parfois je m’assois tout la journée avec des lions, en attendant de les photographier, et à la fin de la journée, les lions se lèvent et à ce même moment, des touristes dans un Land Rover apparaissent sur la colline. Je dois reculer parce que je ne peux pas bloquer leur vue. J’ai passé toute ma journée pour que les lions soient complètement tranquilles, pour que quand ils se lèvent ils ne remarquent même pas mon équipe et moi….mais c’est comme ça. C’est de plus en plus difficile. Souvent, je dois y aller hors saison, mais même ça ets insuffisant puisqu’il n’existe presque plus de “hors saison”. C’est très frustrant.

Est-ce que vous avez de problèmes avec les touristes ou leurs guides ?

Non, ce serait antisocial et injuste pour eux. Il se peut que certains d’entre eux

soient en pleine lune de miel, ou passent les vacances de leur vie, donc ce n’est pas

juste, même si ça me rend fou je dois reculer.

« A Shadow Falls » a était fait en combien de temps ?

Pendant quatre ans, j’ai passé un total d’un an pour faire ces photos. 58 photos, 58

secondes pour un an de temps passé là-bas.

Au-delà de cette année de photographie, il y a aussi le travail de tri et d’impression. Vous faites ça tout seul ?

Je trouve qu’imprimer soi-même est le meilleur moyen de comprendre les erreurs dans la photo,

même si c’est seulement avec une imprimante jet d’encre. J’aime le faire moi-même. Je pense que je passe plus de temps à dire «ah, ce n’est pas bien » ou « les nuances sont mauvaises ».

Donc vous retravaillez l’ensemble continuellement pour améliorer votre travail et pour avoir le résultat que nous voyons ici ?

Ouais.

Comment procédez-vous avant l’impression ?

Je scanne la pellicule noir et blanc et je me sers d’un logiciel pour faire le sépia.

Retournons à la vie de ces animaux, vous avez dit qu’ils sont de moins en moins nombreux. J’ai lu quelque part que vous êtes retourné sur un chemin huit ans après l’avoir emprunté et que vous étiez surpris par la diminution des animaux. Que leur est-il arrivé ?

Il y a une croissance incroyable de la population en Afrique, même si le continent est considérablement grand. Malheureusement, la concentration de nature est aussi la plus importante là où se trouve une grande partie de la population, comme dans le sud du Kenya, ou le nord de la Tanzanie. La population augmente en même temps que beaucoup de pauvreté et il y a ces animaux qui deviennent essentiellement de la viande gratuite. Ils n’ont aucune chance. Ils seront mangés, tout sera mangé. Les lions seront tués parce qu’ils tuent le bétail local. Ils seront empoisonnés et dans pas très longtemps, il ne restera plus rien.

Je vois dans votre travail des vues pessimistes et optimistes. Vous êtes d’accord avec ça ?

C’est bizarre parce que je suis toujours étonné quand les gens me disent ça. Je suis surpris qu’ils ressentent que tout disparaisse. Il n’y a rien dans mes photos qui dise que tout va disparaitre, et pourtant, je ne comprends pas comment, les gens ont ce sentiment. Je ne sais pas pourquoi.

Vous voyez un autre projet après celui-ci ?

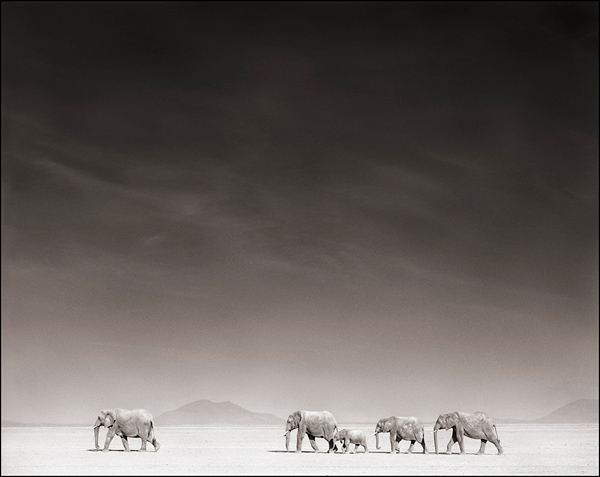

Ce livre est le deuxième d’une trilogie. Le premier était « On This Earth », le deuxième était « A Shadow Falls », et le troisième va finir la phrase : sur cette terre, un ombre tombe… Si vous regardez dans « A Shadow falls » il y a un fil conducteur. Il commence avec le paradis et une abondance d’animaux, du “vert”, de l’eau. En tournant les pages, tout devient progressivement plus sec, et il y a de moins en moins d’arbres et d’animaux, jusqu’à arriver à la fin du livre. Les arbres sont morts et il n’y a plus d’eau. La dernière photo est d’un œuf d’autruche sur le fond d’un lac asséché, ce qu’on peut interpréter de plusieurs manières: y a-t-il un espoir ou au contraire aucun ? Moi, je ne sais pas, mais c’est juste là, laissé comme une pointe d’interrogation qui mène au troisième livre, qui doit aller plus vers le noir, mais je ne sais pas encore comment. Ça va compléter la trilogie.

Qu’est-ce qui vous a poussé vers le sujet des animaux africains ?

J’ai toujours adoré les animaux. En tant que réalisateur de cinéma, j’avais du mal a trouver des contes d’animaux pour adultes. En gros, presque tous les films d’animaux sont pour les gamins. Je ne suis pas très intéressé pour faire un film pour les enfants, même s’ils réagissent à mes photos parce qu’ils sont la génération du futur. De plus, le processus pour faire un film est frustrant hors du tournage en lui-même: on cherche des financements. On attend des années et des années, les meilleures années de notre vie, les années les plus inspirées et pleines d’énergis, en ne faisant rien.

Vivre en Californie, avoir des réunions avec des producteurs et des gens du studio pour un film qui ne sera jamais fait parce qu’il manque de l’argent… Des années peuvent se passer comme ça ! Ça m’a rendu dingue. Je n’en pouvais plus. J’ai eu besoin de créer enfin.

Quant à l’Afrique, j’y suis allé en 1995 pour faire un des clips de Michael Jackson. Je suis tombé amoureux de ce continent. C’était complètement magique pour moi. Je devais y retourner pour mes vacances et c’est quand j’ai amené mon Pentax avec moi que je me suis rendu compte qu’il y avait des moyens de m’exprimer sans avoir besoin de l’argent de quelqu’un d’autre. Au début, ça m’a beaucoup coûté. Je devais réaliser des pubs stupides pour des voitures pour payer mes voyages. Je n’aurais jamais pu prendre ces photos d’une façon normale, comme la plupart des photographes de nature.

Comment travaillez-vous ? Avez-vous un processus différent des autres ?

J’ai une équipe de trois véhicules et une radio pour communiquer. C’est utile d’avoir les autres voitures, pour surveiller les guépards endormis par exemple. Mon équipe peut m’avertir quand les guépards se réveillent. C’est plutôt comme le tournage d’un film. C’est une séance en équipe. Encore un exemple avec les lions : je peux passer 17 jours d’affilée en attendant un lion qui dort et qui se lève le 18ème jour. J’ai plus d’opportunités en travaillant comme ceci ; j’utilise mon temps d’une manière plus efficace. Mais c’est très cher de fonctionner comme cela.

Pour les éléphants, vous avez souvent une lumière forte et un ciel clair tandis que les lions sont photographiés dans une lumière plus faible. Avez-vous de préférence de lumière pour certains d’animaux ?

J’aime photographier avec les nuages parce que j’aime cette sensibilité esthétique plus douce. Une lumière plus forte connote un sens moderne. D’ailleurs, une lumière nuageuse permet de voir dans ces animaux avec leur apparence et leur graphisme propres, sans la complication du soleil et de ses ombres portées. Je trouve aussi qu’une forte lumière et un ciel bleu n’entraîne pas l’atmosphère particulière que je recherche. Si vous prenez mes photos et imaginez un ciel bleu, la photo devient beaucoup moins intéressante. Tout d’un coup il y a toute une espace vide et ennuyeux qui manque d’atmosphère.

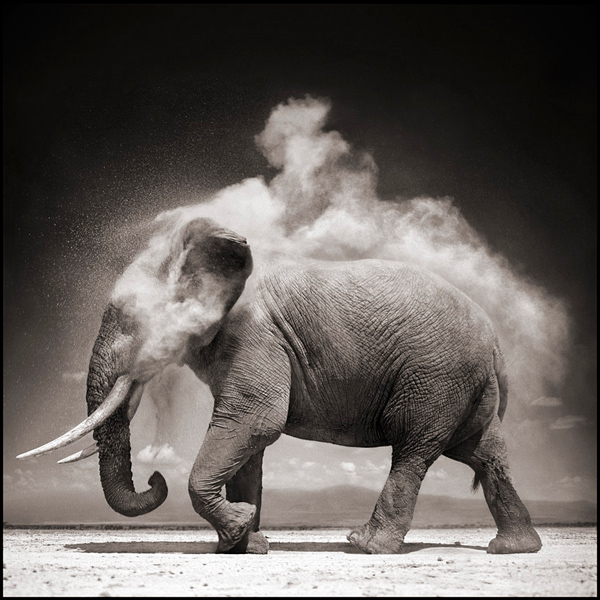

De temps en temps, il y a un ciel complètement clair, comme dans « Elephant with explosing dust ». Mais l’ironie, c’est que la poussière devient nuage.

Pour les lions, quelques heures après l’aube, la lumière devient trop forte et on ne voit plus leurs yeux – c’est juste moche. Ça ne sert à rien de prendre une photo – c’est une perte de temps. Vous ne verrez jamais une de mes photos de lions ou de guépards prise après 8 heures du matin, sauf s’il y a des nuages, et alors ça peut être dans l’après-midi. Pareil pour les gorilles et les chimpanzés. Il faut une lumière nuageuse et douce pour voir leurs yeux, sinon il n’y a que des trous noirs.

Quels changements peut-il y avoir pour mieux préserver vos sujets photographiques menacés ?

La meilleure conservation, et celle qui est éthiquement la plus moderne, se base sur un travail avec les communautés locales qui vivent dans le même environnement que les animaux. C’est la seule manière qui peut fonctionner. Le vrai problème, c’est que même si vous travailler avec les communautés et que les gens comprennent l’importance financière d’avoir des touristes qui viennent pour voir les animaux, il suffit d’avoir 100 mauvais types, qui viennent de 100 km ou 1000 km, avec leurs fusils AK 47 ou leurs poisons. Ils peuvent anéantir la faune très très très vite. Et puis tout ce travail avec les communautés locales n’aura pas porté ses fruits. C’est ce qui arrive depuis quelques années.

Ajoutez la sécheresse – la pire depuis 30 ans – et la crise économique qui engendre un manque de tourisme. Puis il y a les chinois : les nouveaux colonisateurs de l’Afrique. Les chinois répètent toutes les mauvaises choses que les européens ont fait il y a un siècle, mais dans une perspective plus économique. Il y a une explosion de demande venant de l’Est en ivoire depuis quelques années, de $400 le kilo en 2004 à $6 000 le kilo aujourd’hui. Le résultat : il est estimé que 10% de la population des éléphants africains – environ 30 000 éléphants – par an sont tués pour satisfaire cette demande. Partout où vont les équipes de construction chinoise, le braconnage augmente.

Même quand un endroit est protégé, il y a toujours des gens qui rentrent et qui tuent illégalement les animaux pour la nourriture, ou qui ramassent le bois pour le charbon de bois. Ça se passent partout, pas seulement en Afrique. Au Mexique, il y a une réserve de biosphère des papillons monarques. Sur une photo satellite de 2004, on voit que les montagnes sont couvertes de forêts et puis on regarde le même endroit en 2008 et la forêt a disparu. Et ça, c’est dans une réserve, pas en dehors. C’est parti. Donc si tout s’est détruit même dans les réserves, quelle chance reste-t-il …

Pendant un long moment, j’ai cru que les éléphants pouvaient s’en sortir, que l’embargo sur l’ivoire fonctionnait, mais la croissance extraordinaire de la classe moyenne en Chine a tout changé ; ils s’en foutent. Ils veulent seulement l’ivoire. On va devoir tout refaire avec les chinois maintenant, comme l’ouest à appris lentement comment traiter le monde avec respect.

Avez-vous prévu une exposition en Chine ?

Quelle bonne question ! Je sais que je devrais, mais j’ai dit « non » à tout parce que je suis dégouté par ce qu’ils font. Mais, en même temps, je me dis « merde, je dois vraiment dire « oui » pour faire de la pub. » Je ne m’attends pas à changer grand chose avec une exposition. C’est dans les interviews pour l’exposition qu’on essaye de faire ce que nous sommes en train de faire maintenant. Je ne l’ai jamais fait mais je devrais.

Une chose intéressante : il y a un mois que j’ai commencé une page sur Facebook et je peux voir les pays d’où viennent les gens qui regardent ma page. Il y en a d’Inde mais personne de Chine. Je sais que je fais une énorme généralisation et qu’il y a des millions et des millions et des millions de chinois charmants qui prennent soin des animaux.

Propos recueillis par MF à Bruxelles, traduits de l’anglais par LG

Nick Brandt photographs African animals, aesthetics versus barbarism

To meet Nick Brandt, you need patience first of all, as this photographer is highly demanded and extremely busy, case in point: his latest work – “A shadow falls” – was opening in three European capitals within ten days! Lesphotographes.com managed to catch him in Brussels before he left for Paris: patience was rewarded. Nick Brandt is a photographer with a real and genuine passion for his subjects, African animals. His pictures bring this well-known photography genre to another level, adding intimacy and romance. He took his time (and missed his train) to share thoughts with lesphotographes.com on his work and the current condition of African animals.

INTERVIEW :

Do you see “A Shadow falls”, your latest work, as a testament that describes African animals or as a work that should motivate people to protect those animals?

First of all, it’s a last testament. At the same time, those animals are disappearing but that doesn’t mean that we should give up. Like with global warming, anybody with a sense of intelligence knows that global warming is happening and it is getting worse. But that doesn’t mean that we should just give up – we can do things. In the same way, these animals are disappearing really fast and it’s going to get worse but we still have to do a certain amount of things. I’m recording this world as it is now and may never be again. I also want people to help in any way they can and I’m just one part of whatever it may be. It may be environmentalists, it may be photographers… Each of us is trying to inform.

This way of showing animals is different than what we are used to. We tend to think about these photos taken of lions in action for instance, lots of color, and so on. When you first began photographing, did you think about taking pictures as you do portraits in black and white?

No, because I’ve never thought of myself as a wildlife photographer. Even when I was going on holiday as a tourist to Africa, before I started, I had my Pentax 67. I was already shooting in black and white and I always hated 35mm. Right from the very beginning, in my first book, there are a few photos that are from the very first ten rolls I ever shot in Africa; if you look through all my contact sheets, none of it is action. One time, I actually bought a very slight telephoto and I hated it. I tried it for a couple of days and put it away again.

All of your work is shot with a Pentax 67, with a short lens?

Yes.

With this short lens, how do you get close to the models? Is this easily achieved?

No, but it depends – every animal is different and you never know. The difficulty is the number of places that I can get close to animals shrinks because the habitat is being destroyed. All that is left are the parks and then because all the tourists are going to those parks, for me to be alone with an animal becomes harder and harder. I can’t be close to animals when there are other people there because then I’m blocking their view, so it’s antisocial. So, I’ll be sitting all day with lions, waiting to get their photograph and finally at the end of the day, the lions get up and at that moment tourists in a Land Rover come over the hill. And I have to back away because I can’t block their view. I’ve spent all day spending time so the lions are completely relaxed so that when they get up they won’t even notice my team and I… but then that’s it. It becomes harder and harder. I increasingly have to go during low-season, but even then, there is getting to be no off-season. It’s very frustrating.

Do you have any problems with the tourists or tourist guides?

No, it’s anti-social and it would not be fair to them. Somebody could be on their honeymoon, or holiday of a life time and it’s not fair, so even though it drives me crazy, I have to back off.

Over which period of time was “A shadow falls” shot?

Over four years I spent a total of one year to get these photos. 58 photos, 58 seconds for one year of time spent there.

Beyond this year of photographs, there is also the editing and printing and so on. You do this by yourself?

I feel that when you print this yourself, even if it’s on an ink-jet printer, you learn more about what’s wrong with a photo. I like to do it myself. I think that I spend more time saying “oh that’s not good” or “that’s bad grading.”

So you rework in a continuous flow to improve and to get these results we see here?

Yeah.

How do you proceed before reaching the printing step?

I scan the black and white film and I just use software for the sepia.

Coming back to the life of these animals, you said that there is getting to be less and less of them. I read somewhere that you took a trail road eight years after taking the same trail for the first time and that you were surprised to see so many fewer animals. What happened to them?

Basically there is such an incredible population increase in Africa, even though you think of Africa as huge. Unfortunately the best concentration of wild-life is also where an awful lot of the population is, such as in southern Kenya, in northern Tanzania… Just as the population increases with high poverty, you have these animals which are basically free meat: they don’t stand a chance. They’ll just get eaten and everything gets eaten. The lions will just get killed because they’re killing local livestock. So the lions get poisoned and before very long there is nothing left.

I see from your work both pessimistic views and optimistic ones. Do you share this view?

It’s strange because I’m quite surprised when people mention that to me. I’m surprised they get from the photographs a sense that this is all disappearing. There is nothing in my photographs that says this is disappearing. And yet somehow, I don’t understand how or why, people get that impression. I don’t know why it is.

Do you foresee another project after this one?

This book is the second in a trilogy. The first was “On This Earth”, the second book was “A Shadow Falls”, and the third will finish the sentence: On this earth, a shadow falls…. And if you look through ‘a shadow falls’, there is a sequence. It starts in paradise with an abundance of animals, of green, of water. As you turn the pages, it gradually gets dryer and less and less trees, less and less animals, until you get towards the end of the book. The trees are dead and there’s no water left. The final photograph is of the abandoned ostrich egg on the bare lake bed which you can interpret any number of ways. Is there hope in that? Is there despair in that? And I don’t know myself. But it’s just there, left as a question mark that then leads into the third book, which has to somehow – and I’m not sure how – go darker. That will complete the trilogy.

What made you go into the subject of African animals as a photographer?

I’ve always loved animals and as a film maker, I couldn’t find stories meant for adults about animals. Basically, just about every movie with animals is for kids. And I’m not really interested in making a kid’s film although I love the fact that kids respond to my photos, because they are the future generation. And also, film making is completely frustrating and miserable; not when you’re filming, but when trying to get the money. You wait years and years and years, the best years of your life, the most creative years and the years you have the most energy, just not doing anything.

Living in California, having meetings with producers, studio people to talk about scripts that never actually get made because you haven’t got the money… The years just go by like that! And it was driving me insane. I couldn’t stand it anymore. I needed to create.

As for Africa, I went there in 1995 to direct one of the videos they did for Michael Jackson. And I absolutely fell in love with the place. It was completely magic to me. I had to go back on holiday and that’s when I started taking my Pentax with me. I just realized there is a way of expressing my feelings without the need of somebody else’s money. Initially, it cost a lot. I had to direct stupid car commercials to pay for these expensive trips. I could never have taken these photos the normal way, like most wildlife photographers.

What is your way of working? How do you proceed differently?

They drive themselves and they spend very little money. I have a team with me with three vehicles with radio to communicate. It’s useful to have the other vehicles there, for example watching the sleeping cheetahs; they can let me know when they wake up. It’s more like doing film. It’s like a shoot with a crew. Another example with the lions: I can spend 17 days in a row going back to that same lion with the wind waiting for it to wake up and on the 18th day it does. I get the opportunities working this way, and I’m using my time more efficiently. But that’s really expensive to do it in such a way.

Do you have a certain preference for certain lights with certain animals? For elephants, you usually have a strong sun and clear sky whereas the lions are shot more in dim lights…

I like shooting in cloud, because I like the softer aesthetic sensibility of that light – the hard light of the sun has too modern a sensibility. Also, cloudy light allows one to see the iconic graphic shape of the animals without sun and shadow complicating the shape.

I also find hard sun and blue sky usually very unatmospheric. If you take a look at a lot of my photographs and imagine, instead of the clouds, a clear blue sky, the photograph will be much less interesting. Suddenly there is all this boring empty space with no atmosphere.

Now, occasionally, there is a completely clear sky, like with the “Elephant with exploding dust”. But the irony is that the dust is the cloud. With lions, within a couple of hours after sunrise the sun gets too high and then you just can’t see their eyes and it’s just ugly. There is no point in taking a photo and wasting your time. You’ll never see a photograph of mine of lions or cheetahs taken after 8 in the morning, unless it’s cloudy, and then it can be the middle of the day. The gorillas are the same, the chimpanzees are the same. You have to have that cloudy soft light so you see into their eyes. Otherwise you just have black sockets.

The elephants are interesting because I love shooting them in clouds because there is, again, that lovely soft charcoal light, but they can also look good in high light because they have these fantastic boney skulls and the way the sun creates contours. Then you can’t photograph them in sun towards the end of the day because then it flattens out all the texture on the contours. So there are a lot of rules I have that mean that I go days and days and days and days without even picking up my camera. I’m just sitting there, going crazy because I’ve come in the rainy season but there is no rain, and there are no clouds, only blue skies.

How could things evolve towards a better preservation of your endangered photographic subjects?

The best conservation, the most modern thinking conversation is all about working with the local communities that live in the same environment as the animals. That is the only way it can work. The problem is that, even when you do that and even when the local communities understand the importance of the economic benefits that they will gain by having all these tourists coming into looking at these animals, you still only need 100 bad apples with guns and poison to come in from five hundreds miles away, a thousand miles away. With their AK 47, or with their poison, they can just wipe out all that wildlife in a very very very little time. Then, all that work that local communities have been doing is for nothing. And that’s what’s been happening in the last years. Add to that the worst draught in 30 years, the economic crisis so there is a huge drop off in tourism. Then there are Chinese: the new colonialists of Africa. And everything that was so bad about what the Europeans did a century ago, now the Chinese are doing it in a different kind of way, more an economic colonialism.

There has been an explosion in demand for ivory from the Far East in the last few years. It’s gone from $400 a kilo in 2004 to $6000 a kilo today. As a result an estimated 10% of the African elephant population – about 30.000 elephants a year – is being wiped out to satisfy that demand.

Everywhere the Chinese road construction crews go, the poaching increases. So, if you are a poor African, who earns maybe 100 or 200 dollars a year, it’s hard for you to say no to the money to go kill an elephant for its ivory. They need to feed their family. I don’t blame the local Africans. The persons to blame are the rich First World, or the Chinese, or whatever, the people who want the ivory, or the people who want the gorilla hand to make an ash tray, or whatever the hell it is.

Then also, again in spite of all the best efforts, even when an area is protected, you still have people coming in and illegally killing the animals for food, taking down the wood for charcoal for firewood. And that is not just in Africa but everywhere. In Mexico, there is the Biosphere reserve for the monarch butterflies: in the satellite photo in 2004, the mountains are covered in forest and you look at 2008 and it’s gone. And this is in the reserve, it’s not outside. It’s gone. So if everything is getting destroyed even in the reserves, what the hell chance is there…

You can keep throwing money in for preservation. For quite a long time I’ve felt very secure that the elephants were going to be ok, that the ivory ban was working, but the incredible fast explosion of the Chinese middle class has changed everything; they don’t give a fuck. They just want the ivory. You have to do it all over again with these Chinese now. Like the Western World slowly learned to treat that world with respect.

Have you planned to have an exhibition in China?

That is a good question! I know that I should because I said “no” to it all because I’m so disgusted by what they do, but at the same time I go “shit, I really should agree because then I can do publicity”. I don’t expect to make that much change with the exhibition. It’s when you do the interviews that go with the exhibition that you try to kind of, what we are talking about now. I should and I haven’t.

One of the interesting things, I just started a Facebook page a month ago and I go on online and see which countries people are visiting from. Lots from India, but China: no. And I know I’m making a huge generalization and there are millions and millions and millions and millions of lovely Chinese who would care about animals.

MF in Brussels